India can grow fast with or without Narendra Modi

India’s five southern states are ruled by largely regional parties that are rivals of the BJP, and some have thrived.

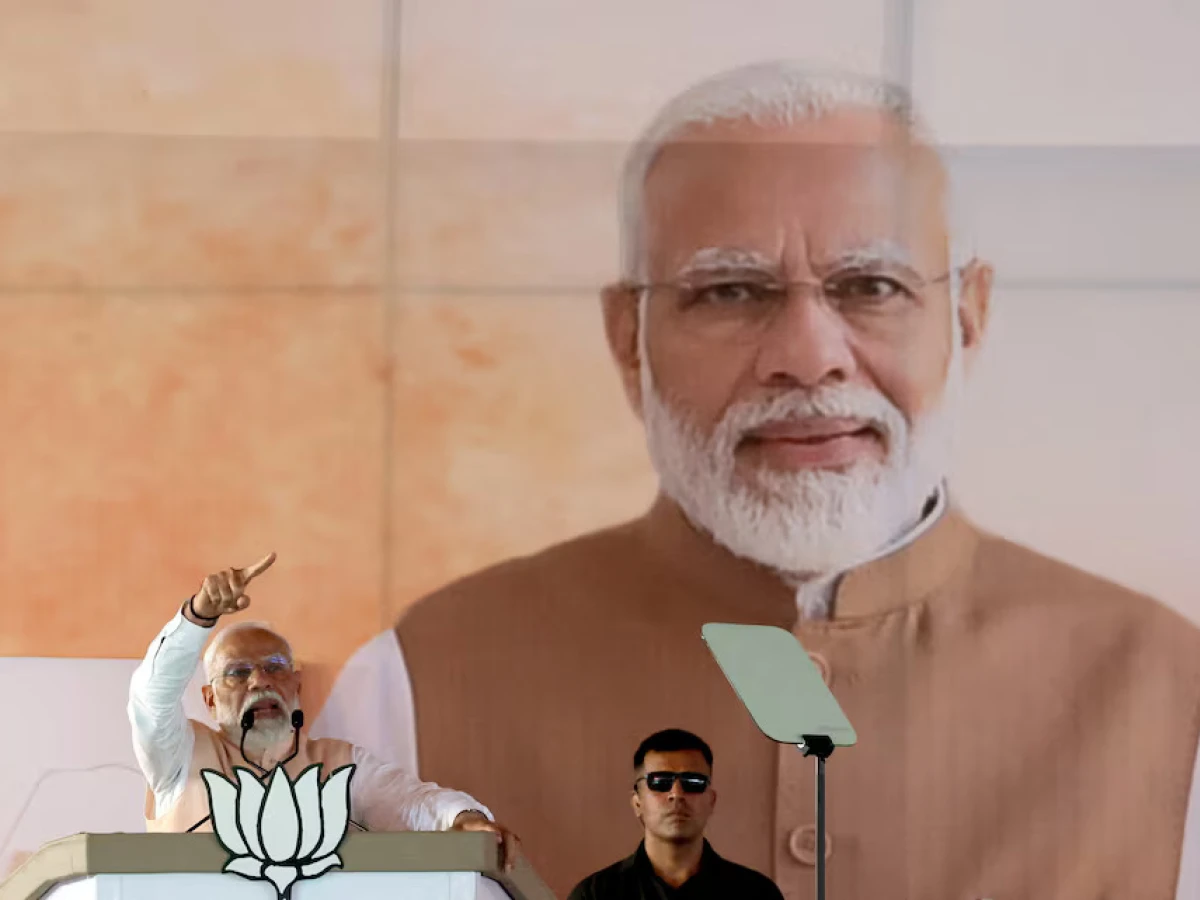

MUMBAI, April 10 (Reuters Breakingviews) - India is about to stage the world’s biggest election from next week, but Narendra Modi can already claim credit for the next decade of growth. While the world economy struggles, the Asian behemoth will keep motoring. The prime minister is hot favourite to win, but his country’s economic development doesn’t depend on him.

Modi’s Hindu nationalist government is so confident of securing a third term that it’s already mapping out future goals. "We see 6%-8% consistent growth rate over the next full decade", a top minister told Reuters in January.

Now, Beijing will be looking to hit its 5% GDP growth target this year. And that means China's factories will keep chugging along.

It's an impressive-sounding forecast, especially because the world economy is likely to experience sluggish growth, opens new tab in the coming years. But it’s also wide enough to mask diverging outcomes. Sure, near the low end of that range, India - currently the world’s fifth largest economy - will overtake Germany and Japan by 2028. Yet even if output expands by 8% a year, India would fall short, opens new tab of its goal of achieving developed country status by 2047, the 100th year since it won independence from British rule.

In any case, India will have to improve on its previous ten years. The economy has grown at an average annual rate of 5.8% since Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party swept to power in 2014. That’s no mean feat, given that it ruled through a global pandemic. Even before Covid-19 struck, India's economy had a reckoning with bad corporate debt and was hit by Modi’s ban on high-denomination banknotes.

Still, the prior government had presided over nearly 8% average annual GDP growth between 2004 and 2013, albeit underpinned by reckless lending that caused a financial crisis.

Modi has tackled some of those issues, cleaning up the financial system, and pushing through reforms such as a bankruptcy code, a levy on goods and services and new real estate rules. India today is more efficient, more open to foreign capital and has better protection for creditors. The government has also made it harder to dodge taxes.

On its current path, India can achieve at least 6% average annual growth by the end of the decade, says Santanu Sengupta, Goldman Sachs' India economist. Increasing overall investment and labour force participation ratios up to previous highs could add another 150 basis points, and, with a few more reforms – including in land and labour markets - long-term potential growth of 8% is achievable, he adds.

Economic optimism is justified. For a start, India's "twin deficits", in its fiscal and current account balances, are now under control. Exports are booming, especially in IT services with companies following Walmart (WMT.N), opens new tab and JPMorgan (JPM.N), opens new tab to set up global capability centres – an evolution of back-offices - in the country. Double-digit headline inflation is in the past and the rupee is trading in a remarkably tight range – good news for companies and investors focused on U.S. dollar returns.

SURVIVING OR THRIVING?

But quickening the economic pace will require India Inc to do more. Public and private investment accounts for about a third of India’s GDP, below a peak of 40% in 2010 to 2011. The government increased its share during the pandemic, but it needs to cut back to curb public debt that reached 82% of GDP, up from 70% in 2018.

The country's richest man, Mukesh Ambani of Reliance Industries (RELI.NS), opens new tab, recently made headlines by throwing a lavish pre-wedding party for his son with Meta Platform’s (META.O), opens new tab Mark Zuckerberg and pop star Rihanna in attendance. But he and fellow tycoon Gautam Adani of the eponymous group, are also spending billions of dollars on renewable energy projects. Less powerful families who were burnt during the debt crisis are opting for less capital-intensive projects. Ministers and businesses predict a flood of foreign direct investment, but the annual inflow is shrinking. Growth is also uneven.

“New India" which comprises high-tech manufacturing, IT services and startups, employs 5% of the workforce but powers 15% of GDP, says Pranjul Bhandari, Chief India economist at HSBC. The rest of the economy, made up of small companies and agriculture, is lagging. Some benefits trickle down to rural and migrant workers but for higher, sustainable annual growth of about 6.5%, "Old India" needs lifting up, she says.

Rich Indians are buying expensive Dyson air purifiers and holidaying in the Maldives but overall private consumption, which typically contributes about 60% of GDP, is forecast to grow at 3% this year - the slowest pace in two decades - despite net household savings sitting at a 50-year low. Some 800 million Indians are poor enough to qualify for the government's free food grain scheme for another five years. That implies most Indians are surviving rather than thriving, opens new tab.

Indeed, the population is booming but so are its struggles in finding employment. Their interest in working at current wages has also declined. The ratio of the working-age population in the labour market has dropped, opens new tab to 55%, from a high of 61% in 2000.

THE MODI FACTOR

For all of Modi’s successes he represents neither the start nor the end of India’s growth story and challenges.

His government provided bank accounts, built toilets, and offered free cooking gas to help the poor, but it also met fierce resistance where change is overdue. He tried and failed to overhaul India’s farming sector, which remains hugely inefficient: agriculture generates just 15% of GDP even though more than half the population relies on it for its livelihood. The government is also in a race to find the immense resources needed to fight climate change. Any leader would hit similar hurdles trying to push for the next leg of reforms.

But growth does not depend on Modi either. Stocks would probably tumble if he were voted out and a return to coalition government might slow down policymaking. But his reforms are hard to reverse and the opposition alliance, led by the Congress party that ruled India for decades after its independence, is broadly aligned with the BJP’s business agenda. In past elections both camps have pledged to retain fiscal discipline.

India’s five southern states are ruled by largely regional parties that are rivals of the BJP, and some have thrived. Where the top politicians disagree most is on how much India should embrace its Hindu versus secular identity.

Under Modi, international groups dub India “partly free” and an “electoral autocracy”, opens new tab, where freedom of expression and association is curbed. The government dismisses these categorisations of its democracy as misplaced, but they may worry investors thinking long-term. Such labels also underscore the extraordinary political stability the leader has provided. Modi will almost certainly win India’s elections, but the economy will have to wrestle with rapid growth with or without him.

India will hold its general election between April 19 and June 1. Votes will be counted on June 4. Nearly one billion people are eligible to vote.

More than 2,400 political parties are expected to put up candidates for 543 seats in India’s Lok Sabha, or lower house of parliament.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party is widely expected to win more than the required 272 seats needed for a simple majority.

His main opposition, the Congress party, which has ruled India for much of its time since independence in 1947, formed a 28-party alliance called INDIA (Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance) to jointly fight the BJP.