The Group of Seven is bruised but much needed

The G7’s current problems go deeper than their leaders’ domestic troubles.

LONDON, June 17 (Reuters Breakingviews) - The Group of Seven is the “steering committee of the free world”. Or so said U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan in 2022. If only that were so.

The club of large, rich democracies has struggled with wars in Gaza and Ukraine. Most of the leaders who turned up at the G7’s 50th annual summit last week in Italy are lame ducks. If Donald Trump becomes U.S. president and Marine Le Pen leads France, they could paralyse it.

Co-ordinating the political and economic actions of the United States, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, France, Italy and Canada is more necessary and harder than ever. Failure to hold together would create even more instability in an already troubled world.

When Sullivan made his remarks, the G7 was riding high. It had come together to help Ukraine defend itself against Russia’s invasion. It had also launched a scheme which promises to mobilise $600 billion to help developing countries build sustainable infrastructure in competition with China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Last year, when the leaders met for their annual summit in Hiroshima, Japan, they agreed, opens new tab to de-risk and diversify their economies from overdependence on China without decoupling from it. And when they proclaimed respect for the United Nations charter and the rule of law, it seemed like they meant it.

BEDRAGGLED BUT STILL STANDING

The leaders carried less credibility at last week’s meeting. That is partly because they are almost all in a precarious political position. Only their host, Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, has a firm grip on office. When leaders are weak at home and distracted by domestic problems, their promises on the international stage carry less weight.

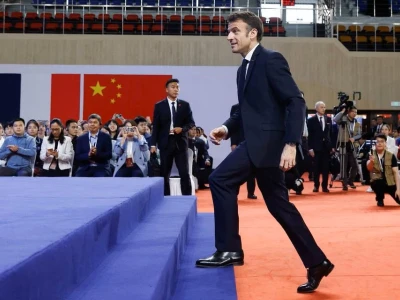

Elections to the European Parliament early this month prompted French President Emmanuel Macron to call domestic elections that could make the country ungovernable. They also undermined German Chancellor Olaf Scholz.

Meanwhile, British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak probably has less than three weeks in office, Japanese premier Fumio Kishida could lose his job in the autumn as his opinion poll rating slides, and their Canadian counterpart Justin Trudeau recently said he often mulls quitting his “crazy job”. Finally, U.S. President Joe Biden has little more than a one-in-three chance of winning re-election in November, according to betting odds, opens new tab.

But the G7’s current problems go deeper than their leaders’ domestic troubles. The difficulties can be summed up in two words: Gaza and Ukraine.

The G7 played a limited role in the world’s response to the war in Gaza. Its leaders did not discuss the issue until last December two months after Hamas attacked Israel. Instead, they initially took different positions on whether there should be a ceasefire. For example, when the United Nations General Assembly called for a humanitarian truce last October, France supported the motion, the United States voted against it, and the other members abstained.

Washington is now pushing for a ceasefire. But its willingness to support Israel despite the mass killing of Palestinian civilians, which a U.N. report says amounts to a “crime against humanity”, opens it to accusations of double standards.

Developing countries, in particular, think the United States has been quick to criticise Russia’s alleged breaches of international law but not Israel’s. That reality undercuts the two top themes the G7 was pushing in Hiroshima last year: upholding the international order based on the rule of law and reaching out to the countries that make up the Global South.

At the same time, the Gaza crisis distracted the U.S. and its allies from the war in Ukraine. It is one of the reasons they were late in providing money and arms to Kyiv, enabling Russian President Vladimir Putin to launch a counterattack this year. If Ukraine loses, the G7 will look weak and its authority in the rest of the world will decline.

The leaders did make some progress at their summit in Puglia. In particular, they agreed the outlines of a $50 billion loan for Kyiv, which will be repaid with interest from Russian assets they froze at the start of the conflict.

NATIONALISM RISK

Whether the G7 will be able to move forward in future years is less clear. Nationalism is on the rise in many countries, and there’s tension between trying to make a country great – often at the expense of others – and being part of a club trying to find joint solutions.

When Trump was president, he refused to sign the G7’s 2018 communiqué and described the host, Trudeau, as “very dishonest and weak”. Le Pen is another potential threat. She may not have to wait until the next French presidential election, due in 2027, to influence policy. Her party could form a government after next month’s parliamentary election.

If Trump and Le Pen were sitting round the table, the G7 may struggle to stand up to Putin. The former U.S. leader has suggested he would not defend European countries against Russian aggression, and Le Pen’s party once borrowed money from a Russian bank.

The French nationalist leader has condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, leading some to hope that she will take a stronger line against Putin if she takes power, much as Meloni did, opens new tab. But any weakening of the G7 could be damaging given that Ukraine will need more money and arms in the coming years.

If Trump and Le Pen are leading their countries, it is also hard to see the G7 making progress on fighting climate change. The former real estate developer pulled the United States out of the Paris climate agreement when he was last president, while the far-right French leader has campaigned against wind turbines.

The G7 has been eclipsed before. After the financial crisis of 2008, the focus shifted to the Group of 20 large economies, including China and India. But its members agree on little and Chinese President Xi Jinping skipped last year’s get-together.

There is a different scenario where peace returns to Gaza, Biden wins re-election, Ukraine holds the line against Russia, and the G7 fulfils its promise to uphold the international rule of law. But that is not the most likely one.