Tajikistan hijab ban sparks intense debate

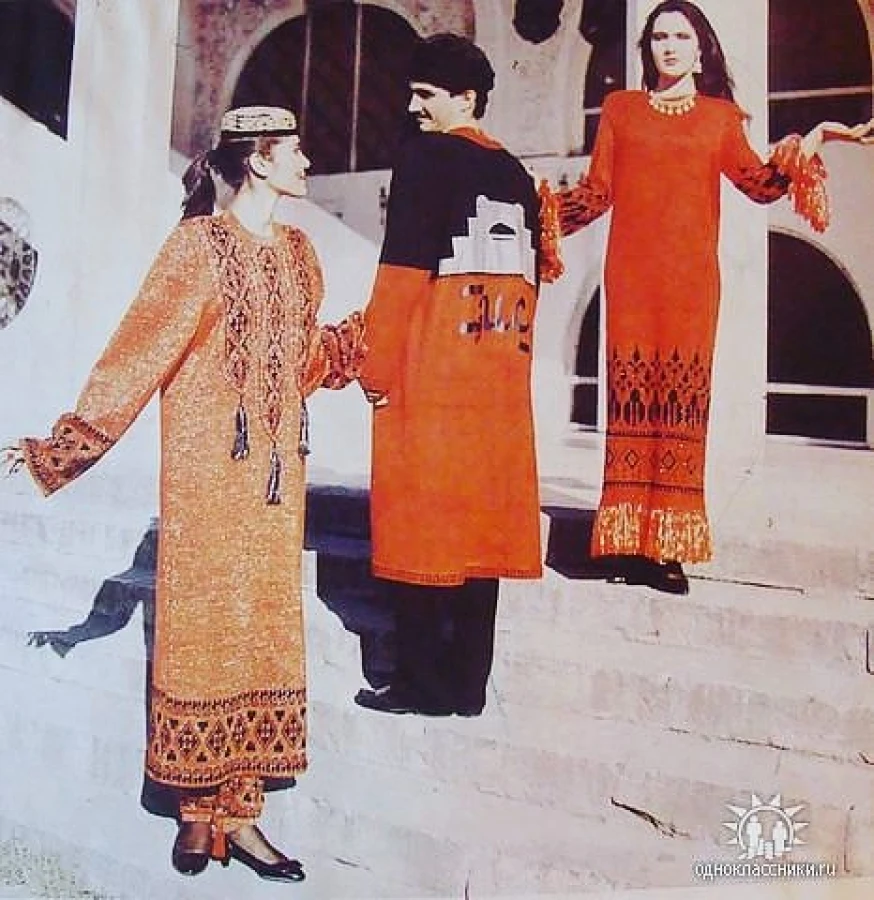

Maldivian cultural outfits are modest, airy, functional and as a bonus, give protection from mosquitoes.

After years of unofficial restrictions on religious clothing, the Tajikistan government has formally banned the wearing of the hijab in the country. The bill, passed by the lower house of Parliament on May 8 and approved by the upper house on June 19, gives legal weight to President Emomali Rahmon's stance against religious extremism.

This decision has sparked a lot of speculation among the Muslim communities worldwide, some with approval and some with disapproval. Bordered by Afghanistan, Rahmon seeks to ban hijabs in a country where around 96% of the population is Muslim.

The new Law

The amended law "On Regulation of Holidays and Ceremonies'' forbids the "import, sale, promotion, and wearing of clothing deemed foreign to the national culture." Central to these changes is the ban on the hijab, the head covering worn by Muslim women, as well as other garments associated with Arab culture. Violators may face fines ranging from 7,920 Somonis (USD 747) for individuals to 39,500 Somonis (USD 3,724).

The men are not exempt from this law, they too face dress code limitations. The government has banned bushy beards, considering them inappropriate. Men are instructed to keep their facial hair trimmed and well groomed. Male students at the nation’s only Islamic University are instructed to wear suits and ties, similar to students at other educational institutions in the country.

The law is part of President Rahmon's broader efforts to promote what he considers "Tajiki" culture and minimise the visibility of public religiosity.

Rahmon has been in power since 1994, making his 30-year rule one of the longest in the region. Early in his career, he positioned himself against more religious political parties, and has a history of opposing certain aspects of Arab culture. In 2015, he referred to hijabs as "a sign of poor education”. Then in 2018, the government even published a manual titled 'The Guidebook Of Recommended Outfits In Tajikistan’, and created a special commission to oversee an “appropriate” dress code for both men and women.

An Eye on Maldives

The Tajikistan hijab ban has sparked mixed reactions among Muslims globally. Some view it as an infringement on religious freedom, arguing that wearing the hijab/niqab is a personal choice and an expression of faith.

Others, however, agree with Rahmon amidst the rising Islamophobia in the west. There are some Maldivians who also link Arab culture to religious extremism. They claim that Maldivian cultural outfits offer appropriate coverage and are practical for the climate of the country, which is ultimately what shapes a civilization’s traditions. They emphasise the importance of respecting a country’s sovereignty and cultural norms. Some even point out how the full black gear creates an environment for crime, conveniently hiding the perpetrator under religious guise.

Rise of the Veil

In Maldives, hijabis soared a decade into the 21st century, with the rise of extremist movements in the country. Then during the second decade, and after the COVID-19 pandemic, many of these hijabis embraced the niqab, which was just a face mask added to their burqa, and their blouses and pants turned into a one-piece abaya.

Before that Maldivian men and woman had their own cultural outfits and etiquette, and it provided the coverage and protection ideal to the Maldivian climate, and were not at all Arab culture. Men wore sarongs that could be flexibly shortened to accommodate time spent in water, which we are surrounded by. Women wore long dresses with long underskirts and gorgeous handmade embroidery, and the women who preferred to cover with a veil did so with very thin and breathable fabric that they just flung across their shoulders. The cultural outfits are modest, airy, functional and give protection from mosquitoes, in a country that is rife with it.

The Almighty is known by the mind and worshipped in his heart, not by the garment, satr, hijab, turban and beard.

Nowadays, however, Arab culture has invaded Maldivian religion and society so much so that the arab keffiyeh, the red and white checkered scarf worn by men in many parts of the middle east has become quite a common sight among the extremist faction Wahhabis in Maldives.

The muslim woman’s hijab, especially the big one worn with the abayas, looks very much like a Christian nuns outfit. This too is a religion that calls for coverage of a woman’s body, but outside the nunnery or convent, this dresscode is not pressured on the women, or used as the only test or measure of faith.

Similarly, Tajikistan’s Kandura (kaftan type long dress) and Paranja (veil) provide adequate covering for both men and women. The long black covering favoured by Arab women is not only foreign to the vibrant Maldivian culture, it is not hygienic either. It can trap heat under the multiple layers of dark, heavy garments and cause several skin and health conditions due to the humidity and rising temperatures in Maldives.

Boiled Down

On one hand, the extreme covering and heavily layered garments borrowed from Saudi Arabia and middle east nations have completely erased Maldivian traditions. School children no longer recognise cultural clothes outside their textbooks, or even know of other cultural aspects of this ancient country.

On the other hand, there are women who wear the hijab and wear cropped and body-fit clothing that do not hide any contours of the female form. Some say it is better to go without than wear the hijab thus. For men, their pants are three quarters in length when religious and their facial hair, like overgrown bushes, captures snot when they sneeze and food when they eat.

The question is not about separating Islamic culture from Arabic culture, but remembering that true devotion lies in not going to the extreme in any direction.